The UK’s trade outlook continues to be shaped by persistent challenges with its three largest partners – the EU, US, and China – while domestic economic constraints limit the government’s ability to support exporters. Brexit-related barriers continue to strain UK-EU trade, potential US tariffs threaten key industries, and diplomatic tensions with China weigh on bilateral trade.

At the same time, the UK economy faces sluggish growth, renewed inflationary pressures, and tight fiscal constraints. Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ commitment to strict borrowing rules leaves little room for large-scale investment in trade infrastructure or financial relief for exporters, raising concerns about the UK’s global competitiveness.

Fiscal Rules and Trade: A Tightrope Act

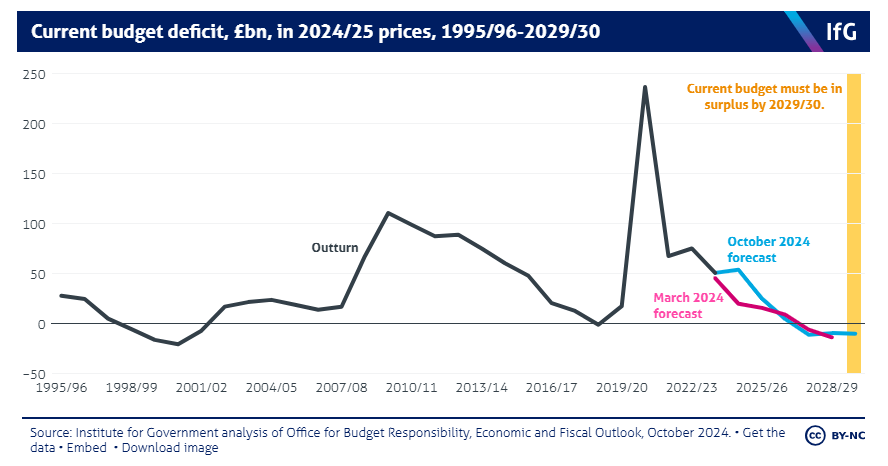

At last autumn’s Budget, Reeves’ fiscal rules maintained market credibility but restricted the government’s ability to counter external shocks and rising debt costs. These rules require day-to-day spending to be funded by tax revenues and public debt to decline as a share of GDP. Fiscal headroom – the government’s leeway to increase spending or cut taxes without breaching its fiscal rules – stood at £9.9bn but has since shrunk to just £3bn as of January, according to Capital Economics, due to a worsening UK economic outlook.

These fiscal constraints limit investment in trade infrastructure and SME support, adding to post-Brexit trade frictions. While fiscal discipline reassures investors, it also limits the government’s ability to cushion businesses against evolving global trade dynamics.

UK’s trade strategy amid a constrained fiscal environment

With limited fiscal flexibility, the government is prioritising regulatory fixes, diplomacy, and fostering private sector investment over direct spending to drive trade expansion. The UK’s strategy includes:

Success will depend on navigating political and regulatory hurdles, as uncertainty continues across all three major trade relationships.

1. UK-EU trade: easing frictions without reversing Brexit

The EU remains the UK’s largest trading partner but also the most complex. Brexit has weakened trade flows, hitting small exporters hardest.

The UK’s exit from the EU’s single market and customs union led to a £27bn decline in goods exports and a £20bn drop in imports in 2022, according to research by the London School of Economics (LSE). While larger businesses adapted, over 16,400 SMEs stopped exporting to the EU after 2021, struggling with new customs procedures, VAT complexity, and rules of origin requirements. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that UK trade in goods and services will be 15% lower in the long run than if Brexit had not occurred, the FT reported.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has ruled out rejoining the single market or customs union and is instead pursuing sector-specific trade improvements to mitigate Brexit’s impact.

Overcoming hurdles

The Centre for European Reform (CER) has outlined areas where UK-EU trade could be improved without reversing Brexit, though progress remains slow:

While Starmer will host EU leaders in May for a Brexit summit, expectations for major trade breakthroughs are low.

2. UK-US Trade: Tariffs, Trump, and Tensions

The prospect of renewed US tariffs under a second Trump administration presents a major risk for UK exporters. While past tariff threats have not always materialised, uncertainty alone is a challenge. The Bank of England (BOE) warns that trade tensions could further weaken UK growth, adding pressure to an already struggling export sector.

The most immediate concern is a mooted 25% tariff on automobiles, with potential levies on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. The UK’s automotive industry is the most exposed, exporting £8.3bn worth of cars to the US in the 12 months to Q3 2024 – 14.2% of total UK goods exports to the US, Office for National Statistics (ONS) data shows. A 25% tariff would significantly reduce demand, impacting manufacturers, supply chains, and potentially jobs. UK pharmaceutical exports to the US were estimated at $7.6bn in 2024, representing 3.8% of total US pharmaceutical imports. While large multinationals would absorb most of the impact, mid-sized UK firms could face disruption.

Beyond sector-specific tariffs, Trump has proposed “reciprocal tariffs” to counter countries imposing VAT on US goods. While the UK applies VAT equally to domestic and imported goods, Trump’s rhetoric frames it as unfair, suggesting a potential broad-based 20% tariff on UK exports. Steel and aluminium exports already face a 25% tariff, which could increase further if reciprocal tariffs are stacked on top of sector-specific ones.

The UK government is working to mitigate these risks, leveraging a statistical trade balance discrepancy to argue for tariff exemptions. The ONS reports a £71.4bn ($89bn) UK surplus with the US, but the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) claims a $14.5bn (£11.6bn) US surplus. The difference stems from the US including trade with the Crown Dependencies (Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man), which the ONS does not. While the UK is using these US figures diplomatically, Trump’s protectionist stance makes a resolution uncertain. The UK is also pushing energy cooperation, increasing US oil and gas purchases to bolster its negotiating position.

3. UK-China: Efforts to Rekindle Dwindling Trade

While US tensions pose immediate risks, UK-China trade faces a prolonged decline due to regulatory and economic barriers. UK-China trade declined sharply in 2024, reflecting weaker demand, China’s tightening import regulations, higher UK compliance costs, as well as geopolitical tensions. According to the ONS, total trade between the two nations fell to £89bn in the four quarters to Q3 2024, a 13% year-on-year decline, with UK exports to China dropping 17.4% and goods exports plunging 27.3%.

The UK maintained a £9bn surplus in services, driven by financial services and intellectual property trade. China’s 5% GDP growth and stimulus measures in 2024 signal potential demand recovery in 2025, particularly in green technology, financial services, and education. The UK and China strengthened financial ties in January with renewed efforts to expand capital market integration and UK financial services access. While UK-China trade remains politically sensitive, Trump’s proposed tariffs on China could redirect Chinese trade and investment toward the UK.

Conclusion

The UK’s trade relationships with its three largest partners – the EU, US, and China – remain in flux, raising idiosyncratic challenges and opportunities. While much of this high-level diplomacy is beyond the control of UK exporters, businesses can adapt by identifying growth sectors, adjusting supply chains, and pivoting between markets where opportunities emerge. Agility in navigating this evolving trade landscape will be essential for sustaining long-term competitiveness.

Daily News Round Up

Sign up to our daily news round up and get trending industry news delivered straight to your inbox

This site uses cookies to monitor site performance and provide a mode responsive and personalised experience. You must agree to our use of certain cookies. For more information on how we use and manage cookies, please read our Privacy Policy.