The UK’s annual trade deficit narrowed by £14bn to £25.1bn in 2024, according to the latest ONS data. However, this masks a growing divergence between services and goods trade. Services exports remain a bright spot, while goods exports continue to decline, deepening the UK’s two-speed economy.

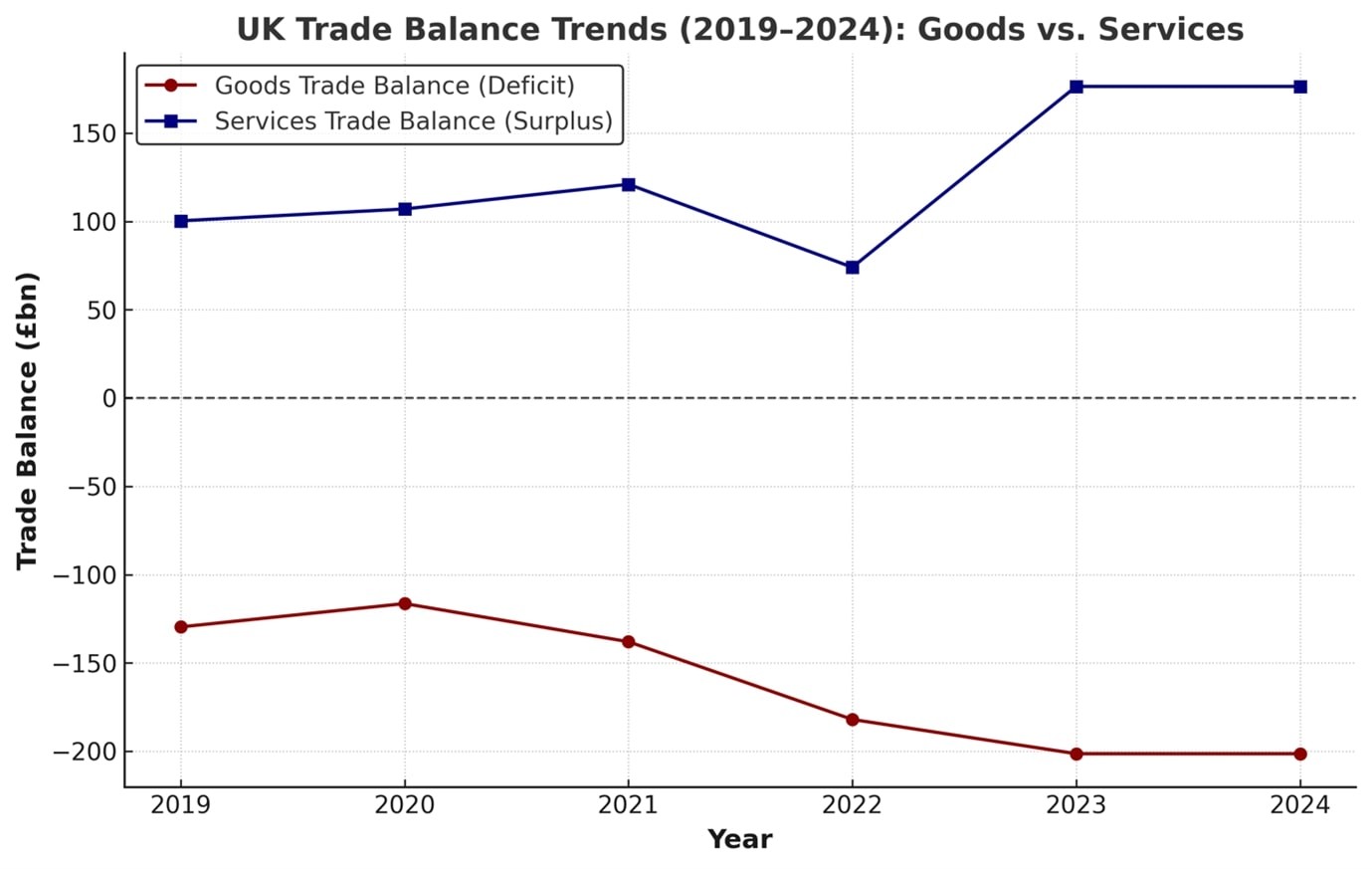

The narrowing UK total trade deficit marks a short-term improvement within a longer-term deterioration. Over the past six years, the goods trade deficit has deepened from -£129.6bn in 2019 to -£201.4bn in 2024, underscoring the structural decline in UK manufacturing competitiveness. However, services trade has proven highly resilient, reinforcing its growing dominance in the UK’s trade model.

Source: ONS

Services exports surged by £24.6bn to £473.4bn, while services imports grew more gradually, rising by £12.3bn to £297.1bn. This expanded the UK’s services trade surplus to £176.4bn, underscoring strong global demand for UK services. However, this recovery comes after a post-pandemic and Brexit-related downturn in 2022, when the services trade surplus fell to just £74.0bn – its lowest level since at least 2019. The rebound in 2023/24 suggests that UK services remain globally competitive, but this sector is not immune to shocks, especially in high-value professional services, R&D, and financial exports. Meanwhile, goods trade continued to weaken, with exports falling by £18.5bn to £359.1bn, and imports declining by £20.2bn to £560.6bn. This resulted in a modest £1.7bn widening of the goods trade deficit to -£201.4bn.

The stark divergence between robust services trade and lagging goods exports has deepened in the post-Brexit period. Quarterly ONS trade data highlights further weakness in the goods trade, with exports to the EU falling by 2.5% and non-EU exports declining by 4.5% in Q4 2024. This underlines the UK’s growing reliance on services to offset weaknesses in its manufacturing and industrial export base.

The faster rise in imports relative to exports highlights three key factors. First, the UK remains heavily dependent on imported goods and energy, and critical supply chains, particularly from its largest trading partners – the EU, the US, and China. Second, sterling’s persistent weakness against major currencies has raised the cost of foreign goods, particularly in dollar-denominated trade, making imports more expensive in GBP terms. Third, post-Brexit supply chain adjustments have led some UK businesses to shift sourcing to non-EU countries, but this has not been sufficient to meaningfully reduce overall import dependence.

December ONS trade data hints at early stockpiling in the US ahead of potential tariffs under the incoming administration, with UK goods exports to the US rising 10.7%. However, EU goods exports fell by 3.9% in December, as Brexit-related challenges continue to stymie UK manufacturers. In contrast, services exports grew by 1.5%, reinforcing the UK’s growing reliance on services to sustain trade performance.

UK trade declined in real terms, despite nominal improvements. Nominal exports increased by £6.1bn, while nominal imports fell by £7.9bn, reducing the overall trade deficit. However, after adjusting for inflation, real exports fell by £4.5bn, and real imports rose by £5.8bn, widening the real trade deficit to £59.6bn.

This indicates that the improvement in nominal trade was price-driven, while actual trade volumes declined, reflecting weaker demand, trade frictions, and shifting supply chain strategies. Goods exports, in particular, fell sharply in both value and real terms, exposing long-term competitiveness challenges for UK manufacturing. UK trade intensity (exports plus imports as a share of GDP) has lagged behind other G7 economies since the pandemic services exports have remained resilient, particularly in high-value sectors like consulting and R&D. According to the Institute of Directors (IoD), consulting, research & development, and high-value services have been top performers, while financial services growth has been less strong, somewhat impeded by Brexit.

As the UK’s trade model becomes increasingly service-driven, goods exports face mounting structural pressures, including Brexit-related costs, global competitiveness challenges, and new tariff risks. Addressing these will require a strategic reset of UK-EU trade relations, more effective implementation of new trade agreements, and stronger efforts to reduce trade barriers and mitigate potential tariffs to support UK exporters, particularly SMEs.

Monetary policy and GDP outlook

The Bank of England (BOE) cut interest rates by 25 basis points in February – the third reduction in seven months – taking the Base Rate to 4.5%, despite an upwards revision to its inflation outlook. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is looking past a near-term inflation surge, expected to peak at 3.7% in Q3, driven by transient factors (e.g., energy prices, VAT changes, and regulated cost increases). A looser labour market further ensures that the 2021-22 inflationary period will not produce the same outcome this time.

Upcoming CPI data (19 February) is expected to show inflation reaching its highest level in 10 months, at 2.8% year-on-year. The MPC is still expected to implement three more 25 bps rate reductions in 2025, dropping the Base Rate to 3.75%.

The MPC has halved its UK GDP growth forecast for 2025, from 1.5% to 0.75%, reflecting mounting economic headwinds. It follows a 0.1% quarterly rise in real GDP in Q4, as ONS data shows, with service sector growth responsible for preventing negative growth. Weak productivity growth, near-term inflationary pressures, sluggish domestic demand, and a weaker global economy – particularly in the Eurozone – have all contributed to the GDP downgrade. Higher business taxes and rising unemployment – which BOE expects to reach 4.75% by 2027 – put further pressure on economic activity.

Implications for SMEs

For UK exporters and importers, especially SMEs, the economic backdrop remains challenging. Sluggish demand in key export markets, particularly in the EU and US, is likely to weigh on orders, while inflationary pressures may keep input costs elevated, squeezing margins. A strong US dollar continues to make UK exports more expensive in the American market, dampening demand further. Meanwhile, ongoing supply chain disruptions and uncertainty around potential US tariffs could increase costs and complexity for international trade.

However, SMEs that can adapt to shifting trade patterns may find opportunities in emerging markets, digital trade, and supply chain resilience strategies. Some relief may also come from falling global commodity prices, particularly in energy and raw materials, which could help reduce input costs. Additionally, lower borrowing costs could provide relief, particularly for businesses reliant on trade finance. With interest rates expected to fall further in 2025, businesses of all sizes may have greater access to financing, not just to manage risk, but to expand exports into new markets. BTG Advisory is well-placed to assist in raising finance for businesses looking to expand export trade or navigate supply chain adjustments. Do not hesitate to get in touch with our team to discuss your circumstances in confidence.

Beyond structural trade challenges, the UK’s trading relationships with the world’s three largest trading blocs remains unsettled. The second article in this series will explore these relationships and assess how trade policy shifts and geopolitical tensions may shape UK trade in 2025.

Daily News Round Up

Sign up to our daily news round up and get trending industry news delivered straight to your inbox

This site uses cookies to monitor site performance and provide a mode responsive and personalised experience. You must agree to our use of certain cookies. For more information on how we use and manage cookies, please read our Privacy Policy.